Opinion

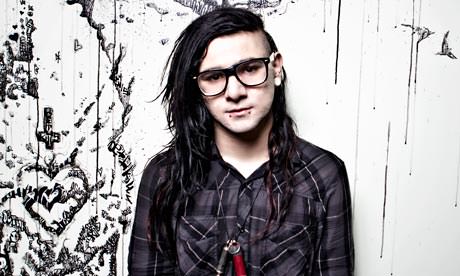

Is Skrillex the Most Hated Man in Dubstep?

Is Skrillex the most hated man in dubstep?

As Skrillex, Sonny Moore has infiltrated the US charts and remixed Lady Gaga and Bruno Mars. Joe Muggs meets the man the underground loves to loathe

Sonny Moore is one happy dude. Sitting on the roof of his UK record label’s office with a mid-afternoon Jack Daniel’s and Diet Coke in one hand, and a scuffed BlackBerry in the other, he’s full of the joys of life. Moore is glad to be catching up with friends in London, excited about the festival he’s playing the next day, and stoked about unveiling a new video he hopes “is going to blow some minds”. This isn’t in a manic way, either – he’s relaxed and lucid. He just seems happy.

Which is encouraging, but perhaps a little incongruous given that, as Skrillex, Moore has become dubstep’s most hated producer in certain quarters of the internet. One thread on the messageboard for Coachella festival, entitled “I never realised how horrible Skrillex was until now” managed to accumulate 1,485 posts. Evidently, many fans of an underground UK genre have not taken kindly to a Los Angeleno Korn fan who dresses like an emo kid, and who used to be the singer for the screamo band From First to Last, taking dubstep to daytime radio and the pop charts.

Nevertheless, Moore is riding a spectacular wave of success. And for all those who hate him, there are many more who adore his music. Barely three years since he reinvented himself as Skrillex, he is the figurehead for the current unprecedented explosion of electronic dance music – including a high-sugar, hyperactive version of dubstep – into the middle American mainstream.

His fidgety sound, which veers from turbocharged disco in the Justice/Daft Punk mould to noises that take dubstep’s “wobble” to an extreme that suggests Satan belching, has defined a generational moment. He plays to vast, demented crowds on a daily basis, remixes the likes of Bruno Mars and Lady Gaga, is around 50 times more searched for on the popular online DJ store Beatport than any other producer, and parties with Tommy Lee. It would take some staggering self-absorption to be miserable in his shoes.

The current standard narrative of fame, especially for US stars, would have him explain how the “haters” make him stronger, how he overcame this or that crippling disadvantage and was now showing all those who doubted him how strong he really is. Moore, however, doesn’t see it that way. “I never really even hear these views, mainly because I don’t have much time for the internet,” he says. “I go to shows and all I see is love. I didn’t even know people had an issue until someone said: ‘Oh, this and that forum seem to have a real problem with you.'” Since he averages more than a show a day, with more than 300 under his belt this year, perhaps his tendency to notice screaming glowstick-flinging ravers over griping keyboard warriors isn’t surprising.

He was “emo with good reason” as a teenager, he says: “I discovered I was adopted when I was 16. But not only that, I found out that everyone – my parents’ friends, my own friends, my friends’ parents, everyone – had known except me. I’ve made up with my parents now, but I wasn’t too happy at the time.” Indeed, he took off with From First to Last to start a life of touring that hasn’t stopped “for more than a month or so” in the intervening seven years.

But Moore is free from self-pity. And he doesn’t suggest that the episode was some kind of dramatic epiphany. Rather, it just made him act on his desire to pursue music. At 13 he started going to punk gigs in “mainly Mexican parts of town”. Later came illegal warehouse raves and sneaking underage into clubs. Like most rock kids of his generation, from an early age he had a working knowledge of electronic music through listening to industrial bands such as Nine Inch Nails, and an obsession with “IDM” (“intelligent dance music”), in particular “anything on Warp Records”.

The other thing his leap into a life on the road revealed was a Stakhanovite work ethic. Asked where he fits sleep alongside gigging and making music (much of which is recorded on the tour bus), he replies: “I don’t. But I don’t do hard drugs all the time either. People always say it must be some cocaine lifestyle, but nobody could sustain that and do all the shows I do.”

There doesn’t seem to be a material goal, just a desire – naive, maybe, or even old-fashioned – to be part of music scenes and to connect with crowds. “I don’t even try to make ‘dubstep’,” he says, lifting his hands to make air-quotes. “It’s just another tempo and rhythm that I work in, because it makes people go wild.” This might sound like a line from Spinal Tap, but his sincerity is endearing.

Moore’s self-image tallies with the view of British dubstep star Skream, who has stood up for Skrillex against more-underground-than-thou snobs. “His production is so fucking clean but twisted,” Skream says, “but the real thing is how he’s shaken everything up without even knowing it. He’s almost done to dubstep what me and Benga did to garage.”

Whether or not Moore takes credit, his electro house and amped-up dubstep sound has found its way into the fabric of American subculture in a way no other rave genre has before. It’s the demented flipside of David Guetta bringing Euro house into the mainstream. And while metropolitan hipsters sneer at dweebs, rednecks and “bros” donning UV facepaint and throwing shapes at commercial festivals, Moore is overjoyed to witness their thrill of discovery.

“I love that people find their own way to react,” he says. “It doesn’t matter if it’s some place with lots of clubs where people are used to dancing. It might be some place in Arkansas where they’re only used to rock clubs, and they react in this very different physical way – but it’s all good, it’s still sexy!” Skream backs this up: “It doesn’t matter where you go, LA or Colorado, the energy out there at the moment is insane, thousands of people go absolutely crazy at every show.”

Perhaps current American dance culture is a bit preposterous, related to “real” house and techno only in the same way as the heavy metal of the 70s and 80s was to the blues. But it is also a hugely celebratory collective insanity, a world away from the portentousness and individualism of much current hip-hop and rock. Anything that can make a superstar of a lank-haired, slighly gauche enthusiast such as Moore has to have some cultural interest.

He seems to appreciate the ridiculousness of the situation. “We party on tour, of course we do,” he smiles, “and there is nothing better, than once in a while being with my friends, wasted, in a suite that’s almost bigger than the houses any of us grew up in, and thinking back to the little festivals we would do in LA, or the punk shows we would go to, and thinking, ‘Holy shit, this music that I never even meant to be released got us here.'” Is it any wonder he’s happy?