‘Has Europe Become Too Expensive?’ The question is not really a question, but more of a statement, as part of the “global community,” you would believe that you can conduct most business remotely. After all, was not the promise of all of these digital tools that we could collaborate without the need for “face to face” interaction? But, sadly, to close and to put a face to the artist, you often have to meet with people, that means travelling.

Sadly, we know altogether too well what that means. It means the inhuman horribly expensive and extremely stressfull experience of travel. Composing for film companies in European countries means travel to those countries. This inevitably leads to “shit, Europe is expensive…”

Global cities are turning into vast gated communities where the one per cent reproduces itself. Elite members don’t live there for their jobs. They work virtually anyway. Rather, global cities are where they network with each other, and put their kids through their country’s best schools. The elite talks about its cities in ostensibly innocent language, says Sassen: “a good education for my child,” “my neighbourhood and its shops”. But the truth is exclusion.

When one-per-centers travel, they meet peers from other global cities. A triangular elite circuit now links London, Paris and Brussels, notes Michael Keith, anthropology professor at Oxford. Elite New Yorkers visit London, not Buffalo.

Sassen says: “These new geographies of centrality cut across many older divides – north-south, east-west, democracies versus dictator regimes. So top-level corporate and professional sectors of São Paulo begin to have more in

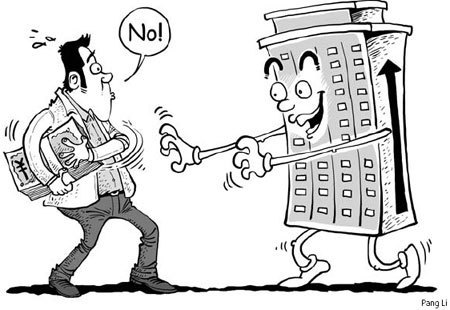

All through history, bright young people migrated to metropolises: think of Dick Whittington, the semi-mythical medieval English country boy who ended up mayor of London. But today Dick wouldn’t be able to afford a bedsit in London. He’d have to turn down an internship. To buy in these cities now, you must either earn a fortune or inherit a house there – and often the same people do both. Outsiders who reach the city late rarely have the education and contacts to succeed.

Inevitably, the one per cent in the global city shapes national policies. Sassen mentions core features of the “neoliberal project”, such as deregulating finance or privileging control of inflation over job growth. “The work was done in Wall Street, the City of London,” she says. Elite opinion-formers, who live in global cities alongside financiers (albeit in smaller flats), assured the little people that these policies would help everyone.

Sassen sighs: “The capture by a very small number of cities of a lot of the excitement and wealth produced by the system – this is a problem.” Outside these hubs, things are less desirable. Most western cities have lost manufacturing. Market towns struggle as small-scale agriculture fades. A few secondary cities (Lyon, Denver, Bristol) thrive. Most don’t. Even cities as prominent as São Paulo, Moscow or Johannesburg may prove too violent or congested to succeed. “You also have cities that simply die – Detroit,” adds Sassen. But if they’re out in the sticks, nobody powerful will hear them scream.